Willis Airey wrote widely on peace and international relations.NZ&P 341.66 A29, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

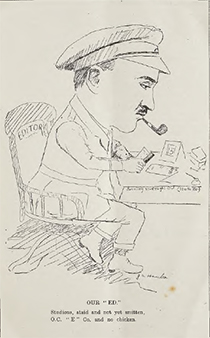

Clifton Firth portrait of Willis Airey, 1955. With permission, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, 34-A185A.

Post-war

Bill Airey made good on his academic promise and did his brother proud. He went back to Auckland University College and completed an M.A. degree in English and Latin, gaining second class honours, then in 1920 went to Merton College, Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship. There he switched to the study of history; this change of intellectual tack, along with the loss of his brother, was the chief impact of the war on him. Michael Bassett, who knew him as a lecturer in the 1950s, attributed the newfound interest in history to a desire ‘to understand war, its causation, and the national and personal tragedies it could inflict’. On his return to New Zealand he secured a position teaching history and English at Christchurch Teacher’s Training College. In 1925 he married Isobel Chadwick, a secondary school teacher who he had met while she was a student at Auckland University College. The couple had three children.

Pacifism

During the interwar years Airey wrote extensively on international relations, concentrating on the question of how to achieve a lasting peace. With J.B. Condliffe, the Professor of History at the University of Canterbury, he founded the League of Nations Union. He was also active in the Student Christian movement, attracted perhaps by its prominent place in New Zealand’s interwar peace movement. Germany’s invasion of Russia swung him towards support for the Second World War. To the end of his life, Airey remained an active and vocal advocate for peace; following the end of the Second World War, he took a leading role in the New Zealand Peace Council and Anti-Conscription Federation, later known as the New Zealand Peace Council, campaigning against nuclear weapons, and opposing New Zealand’s involvement in the Korean and the Vietnamese wars.

Lecturing and writing

By 1929, Bill was back in Auckland, newly appointed to a lectureship at Auckland University College where he taught until his retirement in 1961. His partnership with Condliffe survived the move; in 1935 when Condliffe was preparing a revised 5th edition of his Short History of New Zealand, Airey was asked to contribute two chapters. By 1953 and the 7th edition Airey had chief responsibility for the volume, Condliffe having left New Zealand for a job at the University of California, Berkeley. The book ran to nine editions and was a staple text in New Zealand high schools for decades.

In the 1930s, Airey had another radical change of intellectual direction. As early as 1927 he had criticised the ‘fetish of Empire’ in New Zealand; by the mid-1930s he was an avowed Marxist. Depression-era suffering played a part in his conversion, so too did disillusionment with Christianity, and an eye-opening trip to China, Manchuria and Japan in 1931. By 1941 he was arguing that a durable peace could only be achieved if social and economic conditions within and between states were radically restructured. A prolific writer of letters to the editor and magazine articles, he contributed to Tomorrow, Here & Now, Landfall, Political Science and the New Zealand Monthly Review.

Keith Sinclair and Robert Chapman, two ex-students who went on to become University of Auckland professors, remembered Airey as tempering his views in the classroom; getting his students thinking, not telling them what to think. ‘To young men and women who had grown up in an atmosphere of stodgy, genteel conformism, of Empire Day, of Anzac Day and compulsory school cadets, the discovery of the variety of views that could be held of their world was genuinely exciting.’ Still, Airey’s views were controversial. In 1947, he ended up in hot water after it was alleged that he had told an adult education class in Tauranga that the most pressing international issue was ‘the people against the ruling classes’. The controversy reached the floor of the House of Representatives where Frederick Doidge, the National M.P. for Tauranga, denounced Airey’s views and questioned why such ‘pernicious teaching’ was allowed in institutions upon which the government spent thousands of pounds each year. A row about the limits of academic freedom erupted, with the Lecturer’s Association defending Airey’s right to free speech and conservative members of the College Council moving a motion disapproving of his statements. Council did not formally censure Airey, but did refer the matter to its Adult Education Committee suggesting that it consider closer supervision of courses such as Airey’s.

Airey taught at the University of Auckland until 1961. He travelled extensively, visiting China and Soviet Russia, trying to understand the rift between China and the USSR. Even after retirement he continued to teach a course in Russian history. In his Dictionary of New Zealand Biography entry on Airey, Michael Bassett credited him with a considerable influence on the direction of the New Zealand historical profession. ‘In training many historians of the next generation, and supervising numerous theses, he was responsible for Auckland’s prominence in New Zealand historical research. Airey taught his students to think independently and to question assumptions.’ This, and four decades of peace activism, were the legacies of Airey’s war.

Deborah Montgomerie