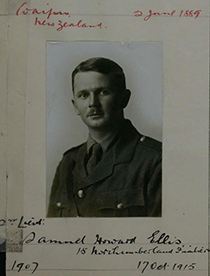

Howard Ellis in military uniform, 1915.Image kindly provided by the Royal Aero Club Trust.

`I have received parcel of provisions and cigarettes… Thank you very much. Thanks, too, for playing cards. Jolly glad to have them, I have also received parcel Xmas fare, marked Weinachtspaket, some pudding; thanks awfully much.’

Ellis, quoted in A short sketch of the work of the New Zealand Prisoners of War Department in London..., London, 1917, p.36. NZGC 940.477 S55.

A barracks at Holzminden with an exposed tunnel through which some POWs escaped in July 1918.Australian War Memorial, P03473.003.

War and imprisonment

By May 1916, Ellis was serving with 6th Squadron, RFC in France. That month, two of his brothers, Roy and Charlie, both signallers in the NZ Expeditionary Force, were by chance near Ellis’ base. Roy recounted how Charlie `… rang up from the horse lines to say that Howard was with a R.F.C Squadron at Estaires, a few miles away. So we rode over on bicycles, and had a great day. We saw Howard’s plane, a very crude affair, which he flew solo.’

Less than a month later, Ellis flew in the aerial raid on the first day of the Somme offensive on 1 July 1916. Two days later while flying near Arras, France, he was struck by anti-aircraft fire which fractured his jaw and left leg and briefly knocked him out. Ellis regained consciousness and control of the plane but had to land in German-held territory and was taken prisoner. He was one of six Collegians who were military prisoners of war (POWs).

During the next 17 months, Ellis was held in nine POW camps and hospitals, an experience he described in an official post-repatriation statement in January 1918.

In his statement, Ellis noted some rare instances where prisoners were treated well and he took care to praise particular individuals, including the `excellent surgeon’ at Crefeld [Krefeld] Town Hospital who operated twice on his leg, nine months after capture.

Mostly, however, his account detailed the harsh conditions prisoners faced in camps and hospitals. His severest criticisms were levelled at the newly-built Holzminden Offizier Gefangenenlager, a camp in Lower Saxony where he spent three months from September 1917. Ellis recited some of the 89 official complaints previously laid with a Dutch envoy who inspected Holzminden under the Hague conventions governing the treatment of prisoners: German rations were `insufficient to support life’ and food parcels were sometimes held back or stolen by guards who, like most Germans, also suffered food shortages. Wood fuel for heating was rarely available and beds were `wooden boards, with filthy mattresses of seaweed, paper or wood shavings’, covered with a sheet and two thin blankets. Prisoners were put into cold, damp cells as punishment for `trivial offences’, including looking out windows and having string, which could be bought in the canteen.

Ellis said: `The whole effect of Holzminden is most harrowing to the nerves. One saw after three months there a noticeable deterioration in health and fitness in nearly every officer – in many cases verging towards insanity.’

The official who took the statement noted that Ellis laid `… great stress on the shortcomings of this place [Holzminden] because it was one of his worst experiences and also because he learnt there that the Germans contemplate the formation of another camp in similar lines in Silesia.’ He said Ellis emphasised that many POWs, particularly the wounded, found it hard to `keep their faculties or minds alert’ because they lacked ‘recreation and useful occupation.’ Ellis had noticed himself stammering and losing `the thread of a conversation.’

When well enough, Ellis started learning German so that he could read local newspapers and books and talk with guards. That fluency proved useful when convincing a German doctor to repatriate a desperately ill British prisoner.

Promoted to Lieutenant while captive, Ellis was repatriated as part of an exchange of wounded prisoners, and arrived in the English port of Boston, Lincolnshire on 7 January 1918.