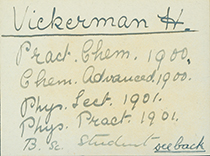

Major Hugh Vickerman. Archives New Zealand, Wellington. R24184909.

`From the billets a walk of little over an hour up the communication trench would bring one to the front line trench along which and in the immediate support trench the mine entrances were located. Each section of the Company had a definite number of jobs allotted to it and these jobs were worked continuously by the three reliefs into which a section was then divided, eight hours on and sixteen off. This was the unvarying routine for many months, eight full hours hard slogging in the solid chalk and flints, till relieved at three, eleven or seven o'clock, then a good hour's plod back to billets along the trench, a rum ration, a hot meal and to sleep till time for the next shift...'

A typical day for the Tunnellers ca April 1916. James Neill, The New Zealand Tunnelling Company, 1915-1919, Auckland, 1922, pp.32, 34.

New Zealand Engineers Tunnelling Company

In September 1915, Britain asked the New Zealand Government to raise a tunnelling company of up to 400 men. Aged 34, Vickerman immediately volunteered his services and was appointed captain in the newly-formed New Zealand Engineers Tunnelling Company (NZETC).

The NZETC arrived in England on the Ruapehu in February 1916 and a month later became the first New Zealand unit to serve on the Western Front. Assigned to counter-mining at Vimy Ridge, near Arras, their mission was to dig underneath the German tunnels and trenches and detonate explosives, inflicting destruction from below. These tunnels could also be used to conceal Allied troop movements and for gathering intelligence.

The Tunnellers’ role relied on how fast they could dig and the New Zealanders, mostly miners, labourers and quarrymen, were three times faster than the enemy and rarely lost a race. They achieved this by being innovative, including creating bigger tunnels which gave them `decent room to swing a pick’ and calculating when they could dispense with supporting timbers.

Between June and November 1916, the introduction of large trench mortars and howitzers began to make the underground war redundant as they wrought destruction more quickly than the miners. The Tunnellers instead set to digging a defensive mining system in front of the British trenches.

The British Third Army then came up with a plan to use recently re-discovered 200-year-old caves and quarries under Arras to reach the German front line east of the city. For five months, the New Zealand Tunnellers opened up and linked the old tunnels and galleries in the Ronville system (which they gave New Zealand place names) so that thousands of troops could be housed and travel underground ahead of a planned assault in early April 1917.

In January 1917, the newly promoted Major Vickerman assumed command of the unit and in April 1917 the Tunnellers reached their objective close to the German front line. On 9 April, the first day of the Battle of Arras, the tunnel exits were blown open and the troops emerged near the German trenches. The Kiwi Tunnellers also detonated three large mines, destroying two German dugouts, a pillbox and around fifty yards of trench. The preparatory work done by the Tunnellers for the battle proved a significant factor in its success and was their `most notable achievement.’

New Zealand Tunnellers in underground bunks at La Fosse Farm, after the Battle of Arras. Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. PH-ALB-419-H355.

New Zealand Tunnellers in underground bunks at La Fosse Farm, after the Battle of Arras. Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. PH-ALB-419-H355.

From May 1917 until mid-1918, the Tunnellers created trenches, dug-outs, machine gun nests, trench mortar emplacements, observation posts and more comfortable billets for the troops. As the war shifted away, the Tunnellers began building bridges, which they proved remarkably adept at. Their first effort, reaching 60 metres over Havrincourt canal, was fashioned by connecting two prefabricated lengths to create what was thought to be the longest single span military bridge.

The Tunnellers continued bridge building for a while after the November 1918 Armistice and arrived back in Auckland in April 1919. Vickerman, however, remained in England investigating engineering projects, including light railways. He returned to New Zealand in October 1919 with his wife Arabella, who had travelled to England in November 1915, a month before Vickerman’s own departure. Newspaper stories reported the couple spent time together in London and elsewhere during his leave and on one occasion she helped host a NZETC dance in Falmouth.

Vickerman received several honours for his war effort. He was Mentioned in Despatches in November 1917 and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) in January 1918 `for distinguished service in the field’ and the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1919 for his services in France.