Robert McFarland.Image: Private collection.

'All we want to see is the Union Jack at the top of the flagstaff and I guarantee they'll hear the cheer in Suva.'

Robert McFarland on the eve of the surrender of German Samoa, writing by moonlight on the troopship Moeraki's bridge.Robert McFarland letters, 29 August 1914. Private collection.

'It's a terrible performance censoring our platoon's mail, reading two hundred letters a week all about the sights of Cairo is worse than a geography lesson, love letters too are of a very poor quality, what the description of Xmas dinner and tucker in general has to do with "being in love" is beyond my knowledge.'

McFarland on being a temporary censor for his unit's mail at Zeitoun Camp. McFarland letters, 31 December 1915.

The stamp shows that this letter survived close reading by another censor. Spragg family papers. MSS & Archives A-264, item 5. Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

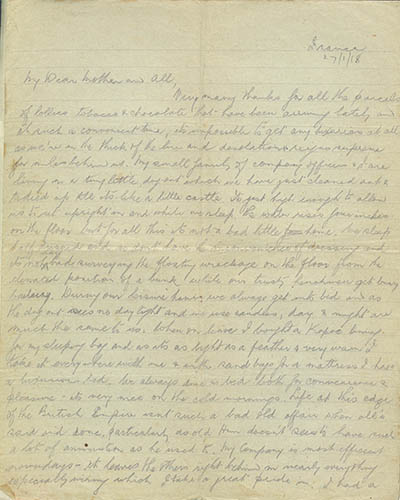

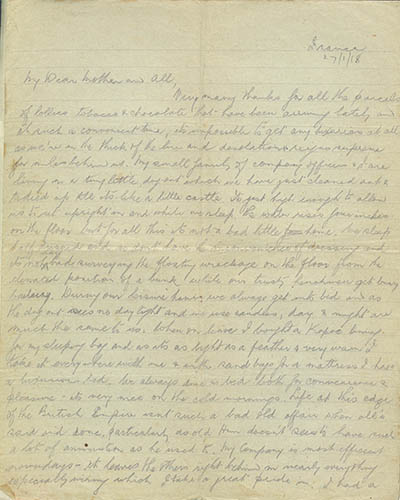

McFarland on the home comforts of his French dug-out in early 1918. McFarland Letters, 27 January 1918. Private collection.

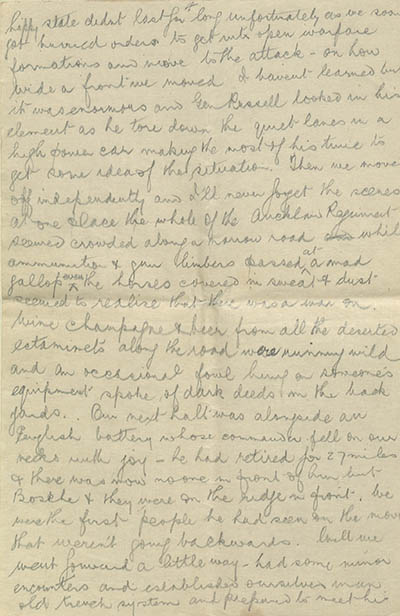

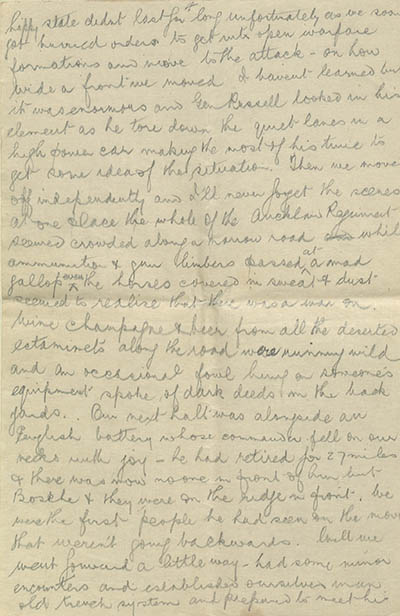

McFarland, writing from hospital, describes part of the action in which he was injured. McFarland Letters, 5 April 1918. Private collection.

Robert McFarland

Robert McFarland’s letters from Samoa and Egypt to his parents convey the ennui of a young law student eager to see combat in the First World War. As an existing member of the territorials, McFarland was part of the force that occupied German Samoa during the first few weeks of hostilities in August 1914. However, it would be almost two years before he reached the battlelines.

Robert Duffus McFarland was one of the three children of Frances and Edgar James McFarland. His father eventually became the senior canon of the Anglican St Mary’s Cathedral, Auckland after a long ministry in the diocese. Robert was educated at Auckland Grammar School (AGS), and was studying law at Auckland University College (AUC) when war broke out.

Samoan Advance Party

As a member of the territorial reserves since 1910, McFarland was at the front of the line when New Zealand was asked to send troops to Samoa. He was attested for general service on 8 August 1914 and left with the Samoan Advance Party of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force four days later. As they approached Samoa after a rough voyage, McFarland recounted to his parents the plan of attack on the ‘eve of the battle’. However, the following morning the island was taken without any resistance, and instead of the expected battle, McFarland and his companions went to the best hotel to enjoy a bath and a five course dinner.

He was stationed in Samoa for seven uneventful months. The monotony was briefly broken on 14 September 1914 when a short standoff ensued after Admiral von Spee steamed into Apia with the cruisers SMS Scharnhorst and SMS Gneisenau. Aside from that episode, and the excitement of periodic rumours of German landings on the island or that ‘one million Englishmen’ had gone to the front and ‘routed’ the Germans, McFarland and his companions entertained themselves by growing moustaches.

McFarland and his fellow servicemen in Samoa were worried that the war was drawing to a close and that they would ‘miss the trip’. They were ‘all dying to get to Europe’ after seeing how many AUC students had left for Egypt with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. After hearing rumours that they were to remain in Samoa for ‘a year or at all events till the end of the war’ McFarland asked for his university notes to be sent over.

His letters demonstrate the enduring ties among AUC Collegians and AGS old boys stationed in Samoa. McFarland also eagerly followed the fortunes of Collegians posted elsewhere, and hoped to send captured German flags to decorate the AUC club rooms and to the headmaster at AGS, ‘as captured by a Grammar Old Boy in Samoa’. Fellow AUC student Robert Proude had his motor bike sent over, and the two Collegians took it on a trip to the Papase’ea Sliding Rocks. McFarland eventually succeeded in leaving Samoa with his unit in March 1915.

Egypt

After returning to New Zealand, McFarland joined the 8th Reinforcements and arrived in Egypt in November 1915, ‘just in time to be too late for Gallipoli after all’. He found Zeitoun Camp to be ‘full of Aucklanders’, and enjoyed socialising with Collegians like Walter Averill. McFarland spent a Sunday afternoon with the AGS College Rifles in early April 1916, and it was ‘almost the same old crowd as when we used to drill together’.

McFarland’s frustration at not seeing any combat continued through the months he spent at Zeitoun Camp. By January, he was jealous of the ‘lucky beggars off to the lines’. This dissatisfaction was increased as news reached him of his classmates that were not serving who had qualified as solicitors.

Keen to ascend the military hierarchy, McFarland took courses in the use of both Vickers and Lewis machine guns, although he was worried that his company would mobilise and leave him behind while he was away studying. He worked for a period censoring outgoing mail from the camp, and was underwhelmed by the quality of the love letters.

Coming from a devout Anglican family, McFarland appreciated the Church of England presence in Zeitoun Camp, and often commented on religious services, including the stylistic differences of the Presbyterian chaplains. Sermons on the ‘evils of Cairo’ soon became monotonous for him. The battalion would pray each morning before going out to drill, which he also appreciated.

France

By the time he reached France in late 1916, McFarland had achieved a commission as a lieutenant in the 16th Waikato Company. On reaching the front line, he maintained his cheery tone although it became strained and would slip occasionally. As his second winter in the trenches of France approached, he wrote that he was ‘enjoying life as much as possible under the circumstances’. He hoped to spend Christmas in England after spending it in Samoa, Egypt, and France over the three previous years. He strongly urged his older brother Kenneth, who had been training for the Anglican ministry, to not come away ‘in the ranks’.

He was appointed temporary Captain of the 16th Waikato Company in June 1917. In March 1918, the Company was ordered to Amiens to meet a German advance. They established themselves in an old trench system and did not have to wait long to face an attack. The fighting was heavy, and a lot of men in the company were killed. The nights were ‘bitterly cold’, and sleep was impossible, but for McFarland, it was still ‘nothing desperate’. Several days into the fighting an ammunition dump exploded right in the middle of their line.

McFarland was shot in the head leading a ‘rush’ on 30 March 1918. He wrote that he ‘had to carry on under rather a disability’, and his ‘undying efforts ended in success’ when a white flag was raised in the opposing trench. McFarland was mentioned in despatches and awarded the Military Cross for his courage, resource, and leadership, and for remaining on duty though wounded. He was evacuated to London and admitted to the New Zealand General Hospital where he enjoyed having ‘a pretty little Londoner to tuck me in at night & wake me in the morning with our tea’. McFarland spent several months recuperating, during which time the headaches and dizziness from the head wound decreased in severity and frequency. Although a doctor noted that he was ‘very nervous and considerably run down’ in August 1918, McFarland had re-joined his unit by October. He was appointed temporary Major in early December, and returned to New Zealand in March 1919, after contracting influenza in London.

Back in New Zealand

McFarland was engaged to Leslie Hunt in March 1920, and they were married in Invercargill soon after. The couple had a daughter in 1921, but the marriage was cut short by his wife’s early death in 1923. He worked in the New Zealand Staff Corps until September 1922, when he returned to the legal profession. He established his own practice as a solicitor in Hamilton in 1924.

He spent the rest of his working life as a solicitor, and reached the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel in the territorials. He married Dorothy Wilson in the Auckland Diocesan High School Chapel in 1929 and the couple had two children, before his second marriage was also sadly ended by his wife’s death in 1937.

McFarland re-enlisted in 1942, and was stationed on Great Barrier Island in command of the 2nd Waikato Infantry Regiment.

Robert McFarland died aged 53 in June 1945.

Jonathan Burgess, Special Collections