'Shells all round us in evening making ground shake some. Fellows made one big dive for bivvies. Had to stop in the middle of this for a "carry" - to take a stretcher case down to the relay, Chitty Post. Quiet carry except for a few M G bullets.'

From Vieira Currie's diary for 15 May 1918.Available online at: Europeana1914-1918.

Vieira Currie

Vieira Currie was studying medicine at Otago when he was called up in May 1917. Just five months later, he was with the 2nd New Zealand Field Ambulance in France, where his war diary shows his medical training was put to good use working at dressing stations and in hospital wards.1

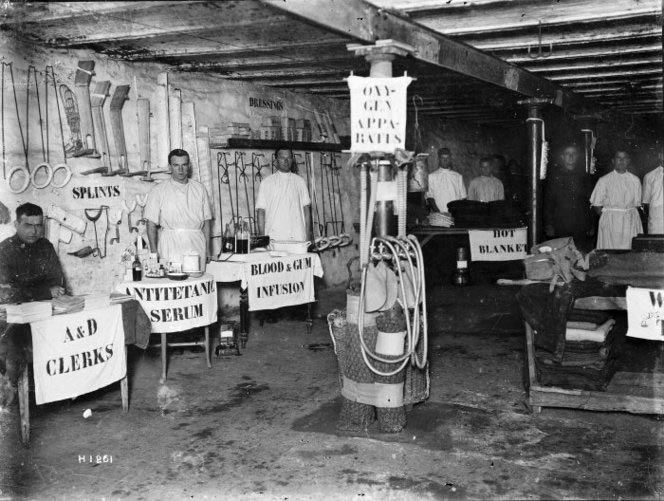

NZ 2nd Field Ambulance hospital interior, (Solesmes, France?).

Royal New Zealand Returned and Services' Association: New Zealand official negatives, World War 1914-1918. Ref: 1/1-002085. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Currie was born in Coleraine, Northern Ireland on 19 April 1897 to Queenie and William Currie, a Presbyterian minister.2 The family emigrated to New Zealand in 1904 to join William’s brother Samuel — also a Presbyterian minister — in the Balclutha district.3 William was called to Kaitangata, South Otago and the family remained there until 1913.

Vieira Currie showed an early aptitude for writing, receiving prizes for ‘ornamental penmanship’, ‘original story’, and ‘collection of post-cards’ at the 1908 Kaitangata Flower Show.4 He was educated at Balclutha District High School, and in 1912 won joint first prize and ten shillings for an essay describing the exhibits at the Clutha winter show.5 He passed the junior Civil Service examination at the end of 1912, just a few months before his father was called to Mangere, and the family shifted to Auckland.6

The Currie family moved into the accommodation provided for them at The Presbyterian manse in Mangere in 1913. In 1915, Currie spent a year at Auckland University College, where he passed examinations in chemistry, practical chemistry, physics, and zoology.7 He then moved to Knox College in Dunedin to study medicine.8

Called up for service

Currie was attested on 16 May 1917, soon after receiving notice of his conscription. He received his training at the New Zealand Military Corps camp in Awapuni, and left New Zealand with the 27th Reinforcements on 16 July 1917 on board the HMNZST Athenic. They disembarked in Plymouth in September, and were sent to France. Currie was posted to Etaples, and arrived there on 19 October 1917, where he was attached to the 2nd New Zealand Field Ambulance.9

He spent most of his time in France in dressing stations, and enjoyed his work there. He was also periodically placed in charge of wards at field hospitals, and sometimes worked as a stretcher bearer, carrying the wounded back from the trenches. He was an eager student and got a lot of practice in the field.10 The front lines were only a few kilometres away so aerial dogfights were frequent occurrences, and shells would often fall in or near the camps.11

The Field Ambulance worked long and hard hours, often through the night. Wounded men would receive rudimentary attention in the trenches before being walked or stretchered to dressing stations, then on to casualty clearing stations or base hospitals as their situation warranted.12 Currie often undertook complicated procedures, including skin grafts. His diary is regularly punctuated with minimal entries that indicate heavy shifts in the dressing stations, after which he was usually too tired to write. After one particular stretch in a dressing station, Currie requested a transfer to a ward, as his hands were ‘going bad’ from the ‘antiseptics, foments etc.’13

Currie wrote frequently about his trips into villages for leisure, and social life in the camps. He helped to decorate the mess room until 2am on Christmas Eve 1917, and the Christmas Day dinner and concert did not finish until 1am. New Year’s Eve was a similarly boisterous affair, with ‘a big noise made, plenty to eat and drink and smoke and everybody happy’. The early months of 1918 included several fancy dress balls and musical entertainments, which Currie enjoyed. However, he found the pantomime staged by the Kiwi Orchestra on 18 February 1918 ‘no good’, as it was ‘too smutty’.14

Currie’s diary shows that his family and friends kept him well-supplied with care packages, and the scarves, socks, jerseys, shaving equipment, soap, meat paste, chocolate, cakes, and café-au-lait that he received were much-appreciated. Currie also regularly received money, with £1 from the sale of his old bike in New Zealand saving his financial situation in November 1917, and a particularly generous £4 sent by his grandmother for his birthday in 1918. Despite the brutality of war, he managed to appreciate moments of beauty, at one point remarking on how exquisite the moonlight through the poplars was on his evening walk on 31 October 1917.15

By May 1918, Currie was in Sailly-au-Bois, between Arras and Amiens, and spent most of the month tunnelling to turn a set of newly discovered underground rooms and passageways — said to date from the French Revolution — into an underground dressing station. He managed to unearth some fossils and a ‘curious specimen’ of what he thought was calcite during this work. Catacombs and tunnels were discovered and put to medical use throughout Louvencourt, Mailly-Mallet, and Sailly-au-Bois.16

After following the Allied advance over the German lines through French towns that were ‘smashed to bits’, Currie got his leave pass stamped and left for London on 18 October 1918. After a fortnight in England, Currie arrived back in France with influenza, but stubbornly carried on with his duties. He was finally hospitalised at the end of November 1918 and ended up in hospital in La Tréport, ‘evidently a fashionable French watering place’. The hospital was based in a beautiful hotel, and Currie was excited to sleep in a bed with ‘sheets etc.’, although he was disappointed to not be with the ‘boys’ in Germany.17

Post-war years

Currie was discharged on 13 May 1919.18 He stayed on in the United Kingdom to finish off his medical training at the University of Glasgow, and received his Bachelor of Medicine on 16 October 1922. He married Mary Donaldson Semple on 10 March 1924, and the couple returned to New Zealand, where their son was born in 1926. The family returned to London in 1931 where Currie practiced until his death in 1937.19

Jonathan Burgess, Special Collections

- Vieira Currie. Diary from 2nd Field Ambulance – France, Europeana 1914–1918, accessed 8 July 2014.

- Vieira Currie. Diary from 2nd Field Ambulance – France, Europeana 1914–1918, accessed 8 July 2014; ‘Currie, Vieira John Spreull – WW1 56140 – Army’, R20994601, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- Register of New Zealand Presbyterian Church, Ministers, Deaconesses & Missionaries from 1840, Court to Cuttle, accessed 8 July 2014.

- Otago Daily Times, 24 February 1908, p.6. Accessed via Papers Past.

- Clutha Leader, 11 June 1912, p.5. Accessed via Papers Past.

- Dominion, 21 January 1913, p.6. Accessed via Papers Past.

- Calendar, Auckland University College, University of New Zealand, 1916, pp.184–186.

- ‘Currie, Vieira John Spreull – WW1 56140 – Army’, R20994601, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- ‘Currie, Vieira John Spreull – WW1 56140 – Army’, R20994601, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- Vieira Currie, Diary from 2nd Field Ambulance – France, Europeana 1914–1918, accessed 8 July 2014, pp.4–5.

- Vieira Currie. Diary from 2nd Field Ambulance – France, Europeana 1914–1918, accessed 8 July 2014, pp.4– 9, 12–13.

- ‘The Treatment of Wounded and Sick Soldiers’, The Long, Long Trail: The British Army in the Great War of 1914–1918, accessed 9 July 2014.

- Vieira Currie. Diary from 2nd Field Ambulance – France, Europeana 1914–1918, accessed 8 July 2014, pp.4–6.

- Vieira Currie. Diary from 2nd Field Ambulance – France, Europeana 1914–1918, accessed 8 July 2014, pp.5–7.

- Vieira Currie. Diary from 2nd Field Ambulance – France, Europeana 1914–1918, accessed 8 July 2014, pp.3, 6, 10, 12, 14, 15.

- Vieira Currie. Diary from 2nd Field Ambulance – France, Europeana 1914–1918, accessed 8 July 2014, pp.11¬–12.

- Vieira Currie. Diary from 2nd Field Ambulance – France, Europeana 1914–1918, accessed 8 July 2014, pp.22–26.

- ‘Currie, Vieira John Spreull – WW1 56140 – Army’, R20994601, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- Vieira Currie. Diary from 2nd Field Ambulance – France, Europeana 1914–1918, accessed 8 July 2014.