Harold Vivian Ramsay

In October 1916 at the tail-end of a long list of military appointments, promotions and transfers, the New Zealand Gazette recorded that 2nd Lieutenant Harold Vivian Ramsay had resigned his commission.1 Behind this brief note lies the story of a distraught man grappling with his scruples and a military bureaucracy grappling with men who baulked at taking up arms.

Vivian (as he preferred to be known) was 27 years old when he asked to be exempted from war service. An Auckland Boys Grammar School old boy, he had initially planned to enter government service, sitting the senior Civil Service exam while working for Government Life Insurance and studying part-time at Victoria University College in Wellington. In 1909 he changed careers and moved to Auckland University College to train as a teacher. A keen sportsman, he played rugby for the university, and participated in debating and the Christian Union.2

Ramsay came from a community-minded family of ‘do-ers’ and ‘joiners’. His father, the long-serving Warkworth postmaster, was active in the local school, library, Presbyterian Church and Masonic Lodge, and was treasurer of the local patriotic fund during the Anglo-Boer war.3 Vivian’s mother, Mary, was caught up in war work, which culminated in her election as the District Carnival Queen in the 1917 fundraising drive for soldiers’ comforts.4 The Ramsays had three sons. Keith, the youngest, was still in school. Rollo, the eldest, felt a keen call to service, but was classified as medically unfit. Interviewed in 1918 about allegations that the salaries being paid to YMCA organisers were too high, he sounded a defensive note. He had ‘enlisted’ as ‘war secretary’ for the YMCA only after failing the medical three times, renouncing a well-paid solicitor’s practice for the chance to serve overseas in a supportive capacity. ‘Every eligible relative’, he assured the reporter, ‘young or old, is “wearing khaki”.’5

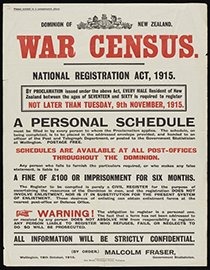

1915 war census poster.Ref: Eph-D-WAR-WI-1915-01. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Men who refused to fight risked being accused of cowardice even when they undertook other kinds of war service. This cartoon shows a young woman confronting her beau after learning he has volunteered for non-combatant service. The cartoonist clearly sympathises with her, depicting the man as shifty, effete and slump-shouldered.Observer, 29 January 1916, p.17.

'... my oath to serve my King and my duty to God are in conflict. Technically at least this is treason and therefore I desire to submit myself to the judgment of the military authorities.'

Vivian Ramsay declares his conscientious objection to the authorities at Featherston Military Camp, May 1916. Military personnel file, R7880700, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

A matter of conscience

Vivian Ramsay was in Featherston Military Camp preparing to go overseas with the 14th Reinforcements in May 1916 when he had his dark night of the soul. He was, on the face of it, an unlikely conscientious objector. Before the war he had been an officer in the territorials, training the Hamilton Boys High School Cadets as an adjunct to his work as a master at the school. He had not gone into camp earlier because rheumatic fever had left him with a weak heart and he had spent large portions of 1915 sick and unfit for military service. He had some qualms about whether Christians could justify their participation in the war but in January 1916 he quietened his doubts and reported for duty.6 Four months later he reported that his faith presented an insuperable obstacle to going to war. `Sir’, he informed the Assistant Infantry Instructor, ‘my oath to serve my King and my duty to God are in conflict. Technically at least this is treason and therefore I desire to submit myself to the judgment of the military authorities.’7

In late 1915 and early 1916 as Ramsay wrestled with his conscience, a political battle was raging over whether New Zealand would introduce conscription. During 1915, districts fell short of their recruitment quotas, and in October 1915 the government instituted a National Registration programme to gather details about every man aged between 17 and 60. The object was to assess how many men were available for service with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. Of the 208,513 men who submitted their details, 109,683 stated their willingness to serve with the NZEF. A further 43,524 were willing to serve in a civil capacity only, while 34,386 declared themselves unwilling to serve in any capacity.8 This evidence that voluntary recruitment would have its limits alarmed authorities and added impetus to the call for conscription. Britain introduced conscription early in 1916, and by mid-1916 a Military Service Bill was before the New Zealand parliament. On 16 November 1916 the first conscription ballot was drawn.

The pressure on all men of military age was immense; for those in families with no sons on active service it was particularly acute. As Ramsay’s hometown newspaper recollected: ‘There was an impression throughout the country that the sons of certain families were evading their responsibilities, and in some cases the wildest statements had been made by people who knew only that certain men looked fit and were not in camp.’9 After the Military Service Act (1916) came into operation, the Defence Department was inundated with the names of men alleged to be ‘family shirkers’. Poignant stories were told of families with five or six sons in uniform, and elderly parents whose only sons had gone to war.10 When Military Service Boards began hearing applications for exemption from conscription, they were required to exempt the last remaining brother in families in which one or more brothers had died; conversely it was part of their job to see that ‘family shirkers’ did not evade their obligations. Concerned citizens sat in judgment on their neighbours’ sons. As one columnist railed, ‘shirker families should be rounded up and made to do their share before others were called on ….’’11

Ramsay was a volunteer, not a conscript. Still, the threat of being labelled a ‘shirker’ hung over him as he struggled to reconcile his faith with his military obligations and the vulgarities of army culture. His qualms resurfaced just before his transfer to Featherston as a platoon officer: ‘I chanced to have lent me a book written by a man whom I had great cause to respect, in which Christian men were challenged to base their attitude in this crisis upon the actual teaching of Jesus Christ.’ Ramsay does not name the book or its author, but its effect was profound. He tried reading it combatively, looking for counterarguments to its pacifist message, and studying what he called ‘the national (and normal) Christian attitude’ to war. It was no good, ‘all I have read and thought has only strengthened the conviction that as a Christian I cannot fight take any part.’ While stressing that he was ‘respectfully’ resigning his commission, he reproached the army for the profanities of his fellow soldiers. Military service coarsened men: ‘the veneer of life is off and men show their true selves.’ ‘How’, he asked, can godless soldiers ‘fight in His spirit or purge themselves of the spirit of hate?’12 He left the nation's service ‘the better [to] serve mankind.’13

This was an agonising decision to make. In declaring himself a conscientious objector Vivian Ramsay was risking financial security and respectability. Between early 1917 and November 1918, 286 New Zealand conscientious objectors were sent to prison. Many were, like Ramsay, members of mainstream Christian denominations who believed the word of Christ prohibited them from participating in the war.14 He was also aware that his loyalty would be questioned and took pains to paint a picture of himself as a patriot: `I come from worthy stock, of Scotland and of Devon. I have been brought up to consider patriotism the very breath of life. I have drunk of the spirit of Kingsley and of Burns, of Tennyson and of Scott. I have loved England well, and love her still. In the present struggle I know surely that if national causes be compared that of England is right and that of Germany damnably wrong.’ Yet, love of country could not quell his doubts about the war’s moral justification. England's hands were not clean: ‘She is in no true sense a Christian nation; her real reliance at this moment is not in God but in material forces - in armaments and in men.’15

`After three years of war men everywhere were sick of the slaughter, home-sick, weary, worn out with the labour, disgusted with the sordidness and the naked, dirty horror of the bloody business. Victory seemed as far off as ever. Mentally, morally, physically, the ordinary man was done. Many talked of a drawn fight, some even despaired of that.'

Ormond Burton describes the mood of the New Zealand troops on the Somme in winter 1917-18 during Ramsay's second stretch at the Front.Ormond Burton, The Auckland Regiment, Auckland, 1922, p.183.

New Zealand Medical Corps

Ramsay could not know how severely his act of conscience would be treated but after several months deliberation his request received a measured and pragmatic response from the army. He was given the option of serving in a non-combatant capacity. There was a sting in the tail though: he was required to refund the cost of his upkeep since going into camp, and the cost of his officer’s uniform and other equipment. Together, these were calculated at £90/10/-. This sum was far beyond Ramsay’s means. He had little savings and little prospect of saving much as a private. He scraped together £10 in cash, which he included with his letter accepting ambulance service, along with an order of £35 against his superannuation savings, and a further promise of an allotment of 3/- a day from his private’s pay. He stressed that while he did not desire any abatement of his ‘real liability’ - to serve his country in time of war - the financial penalty imposed was ‘harsh and unfair’.16 He was saved by the Camp Commandant who argued in mitigation that up until Ramsay ‘got his peculiar conviction’, he had done good work, and that even after resigning his commission, had exerted himself ‘most assiduously in the sanitation of the camp’. In the Commandant’s opinion, handing in his uniform with the cash payment of £10 should suffice. This compromise was approved.17

Vivian Ramsay actively sought front-line service. When he accepted the transfer to the Medical Corps he asked to go to France as soon as possible, ‘to share as far as possible the dangers which my fellow countrymen are facing’. Those dangers – and his determination to share them – were very real. Embarked from Wellington in October 1916, Ramsay reached Sling Camp in late December 1916. He had been promoted to Sergeant in Awapuni, the New Zealand Ambulance training camp in Manawatu, but shortly after arriving in England at his own request he reverted to the rank of private to get to the front with an earlier detachment.

He landed in France in January 1917 and served with the 1st Field Ambulance as a stretcher bearer until being hospitalised in late May with sub-acute rheumatic fever. By November 1917 he was well enough to return to the front line. There he served through the miserable winter of 1917–18 in the blood and mud of the Somme, tending the dead and wounded through some of the worst fighting.

Stretcher bearers bringing in wounded on the Somme, France, four days afterRamsay’s death. Ref: 1/2-013101-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Stretcher bearers bringing in wounded on the Somme, France, four days afterRamsay’s death. Ref: 1/2-013101-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

On 2 April 1918, Vivian Ramsay was killed in action in the small village of Mailly-Maillet, near a New Zealand dressing station. He was mourned. On the first anniversary of his death, his family posted a Roll of Honour notice in the New Zealand Herald that used as his epitaph a quote from the hymn, O Love That Wilt Not Let Me Go, alluding to their son’s faith in Christ and their hope that he had found peace.18

`O Cross, that liftest up my head,

I dare not ask to fly from Thee;

I lay in dust life’s glory dead,

And from the ground there blossoms red

Life that shall endless be.'

Deborah Montgomerie

Further reading:

Paul Baker, King and Country Call, Auckland, 1988.

Tim Shoebridge, Dissent and Conscientious objectors, https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/first-world-war/conscientious-objection.

- New Zealand Times, 5 October 1916, p.7. All newspapers accessed via Papers Past.

- Auckland Grammar School Chronicle, 1918, 6, 1, pp.20-21.

- Rodney and Otamatea Times, Waitemata and Kaipara Gazette (RT), 10 September 1941, p.7.

- RT, 28 November 1917, p.1; New Zealand Herald (NZH), 25 November, 1926, p.12.

- Evening Star (ES), 19 February 1918, p.4.

- Harold Vivian Ramsay to Assistant Infantry Instructor, Featherston Military Camp, 16 May 1916, Military personnel file, R7880700, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- Ibid.

- Paul Baker, King and Country Call: New Zealanders, Conscription and the Great War, Auckland, 1988, p.58.

- RT, 13 August 1919, p.4; see also Wanganui Herald, 14 July 1919, p.5.

- Baker, p.118.

- ES, 7 December 1916, p.2.

- Ramsay to Assistant Infantry Instructor, Ramsay personnel file.

- Ibid.

- NZHistory conscientious objectors spreadsheet, https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/the-military-objectors-list.

- Ramsay to Assistant Infantry Instructor, personnel file; The man who came to be known as the ‘father’ of Christian Pacifism in New Zealand, Henry Urquhart, felt obliged to resign from teaching because of his Pacifist views. He was tried for sedition, jailed for a year, and lost citizenship rights for 10 years. Maoriland Worker (MW), 2 May 1917, p.3; MW, 16 May 1917, p.6.

- Harold V. Ramsay to Adjutant-General, New Zealand Military Forces, 11 July 1916, Ramsay personnel file.

- Lt. Col. N.P. Adams to Adjutant-General, 12 July 1916; Memo, n.d. [July 1916] D. Cossgrove, Deputy Assistant Adjutant-General, Ramsay personnel file.

- NZH, 2 April 1919, p.1. The family placed memorial notices in the newspapers throughout the 1920s and 1930s and both parents’ obituaries noted that their son died on active service, NZH, 25 November 1926, p.12; RT, 10 September 1941, p.7.