Phillips received his Bachelor of Music from AUC in 1909, three years after the first was conferred by the College on Florence Williams. Lectures in music began at AUC in 1888 as part of the Bachelor of Arts degree, but it was not until 1901 that the College secured a piano.

On completing his degree, Phillips left for London to study at the Royal Academy of Music (RAM). During his time there from 1911–1912, his principal study was singing and his second study was piano. He also took courses in harmony, diction, and teaching. After receiving his diploma, he returned to New Zealand. In 1914 he agreed to take up the voluntary position of conductor with the Music Society at AUC. He resumed his responsibilities at All Saints and continued teaching.

War service

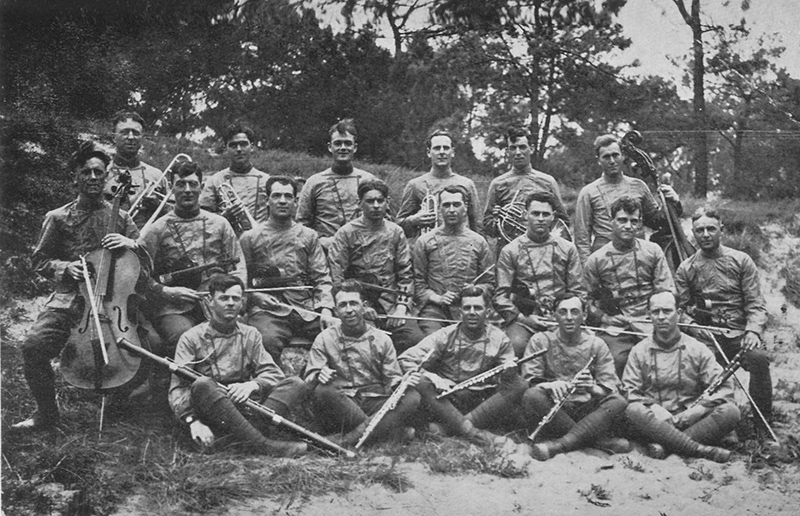

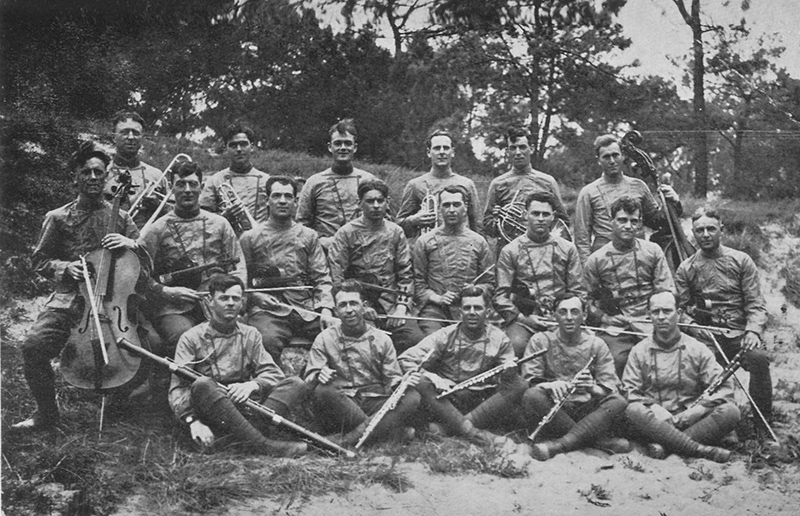

Seymour Phillips, middle row, fourth from right, with the Kiwi Orchestra in Etaples, France in 1918. Ernest McKinlay, Ways and By-Ways of a Singing Kiwi with the N.Z. Divisional Entertainers in France, Dunedin, 1939, pp.112–113.

Phillips enlisted on 5 October 1916, aged 32. After training in Featherston in early 1917, he left New Zealand in April on board the HMNZT Devon and disembarked in June in Devonport, England. He was posted to Sling Camp in Wiltshire where he became part of the Sling Band. Phillips left the camp for France in May 1918, and arrived in Etaples on 10 May 1918.

In Etaples, Phillips joined the Kiwi Orchestra as conductor. The ‘Kiwis’ had just staged their production ‘Y Go Crook’, and the ‘girls’ of the production were drawing large audiences to the marquee on the sands at the back of the New Zealand camp. In June, the orchestra performed in Authie, France for crowds that included New Zealand Prime Minister William Massey and Deputy Prime Minister Joseph Ward. Later in the year they re-staged ‘Y Go Crook’ in Paris after a special request.

Phillips was affectionately remembered by 'Kiwis' tenor Ernest McKinlay as hoping to ‘go into the bush with a nice book, to have a good read and hear the birds sing’ when peace eventually came. After the Armistice was signed, the Kiwi Orchestra marched through Belgium into Germany as part of the occupying force. But, by this time, Phillips was dangerously ill with influenza in an Etaples hospital so did not accompany the unit on its last leg.

By early 1919, Phillips’ influenza had progressed to double pneumonia and the Medical Board recommended that he should be discharged as permanently unfit with a full pension. By the time Phillips left for New Zealand on the HMNZHS Marama in June, he had recovered significantly and he arrived in New Zealand on 17 July 1919 with a full bill of health. He was discharged in August 1919.

After the war

Phillips lost no time in returning to his studies, and left again for England and Europe in August 1924. During the three years he spent abroad, he studied composition and conducting at RAM, spent time with composer Jean Sibelius at his home in Finland, and had luncheon with the Scottish tenor Joseph Hislop, who had previously toured New Zealand.

Phillips interpreted the ‘ultra-modern’ musical tendencies on the Continent in the 1920s as resulting from the ‘excitement that swept over Europe as a legacy of the war’, and was not particularly worried about the vogue of jazz, because he ‘thought it would die down’.

In 1927, Phillips graduated as the first Doctor of Music from the University of New Zealand. He was very active in musical circles in the 1930s, becoming president of the Auckland Society of Musicians, president of the Auckland Classic Club, and a member of the New Zealand Music Teachers’ Registration Board. In 1936, Phillips was elected a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music, an exclusive selection of 150 living alumni who had distinguished themselves in their careers. This was the first time the honour was bestowed on a musician resident in New Zealand. Phillips maintained his association with AUC, and was appointed to lecture in singing and voice production in 1937.

Phillips led the choir at All Saints until 1949. In his later years as choirmaster, he was remembered as ‘portly and silver-haired, pegging along with a brisk, nodding gait towards choir practice, where he lavished on his choirboys the same teaching for which his adult pupils (some of Auckland’s best) paid pounds. Make it guineas.’

Phillips died on 27 February 1961, aged 76.

Jonathan Burgess, Special Collections